This week, as an extended Bank Holiday Bonus, we will be looking at how to outline your novel:

Taking the time to outline your novel can save you grief in the long run. An outline helps keep your story on-track and progressing past the initial thrill of beginning your work. Maybe you can’t wait to start writing, or maybe you’ve already started but are running into problems. This guide will explain all the techniques you’ll need to craft an effective outline for your novel.

***

Establish Your Settings

Setting is vital to every story. It helps a reader fall into your fiction world, even if your story is set in Earth-as-we-know-it. It can also be critical to the plot: imagine if Grandma’s house wasn’t deep in the woods. Little Red Riding Hood may never have met the Wolf.

The setting also tells the reader about your characters. If Little Red lived in a castle, she may have been more aware of dangerous people, and the Wolf’s motives may have been more than hunger.

Setting can become vague in writing when the writer doesn’t know their setting well. The same way you have character profiles, settings need profiles too. The process of planning your setting is slightly different if your story is set in a real place, though it follows the same general steps.

Before you get to know your setting, you need to choose your setting. If you’re stumped for ideas, the best place to look is in your plot. Setting is tightly linked to plot, primarily affecting what is possible. Does a character need to be or feel trapped? Go for a fort, boarding school, or a safe house in the middle of nowhere.

Usually your story will take place in more than one setting, so go through your plot and make note of the best setting for each scene.

When you start working on details of your setting, you may already have an idea in your mind – Victorian mansion, sea cliffs, military base, Sydney Opera House. Even if you feel familiar with the setting, go around with a camera or search images online.

Make note of what aspects you notice first: is the colour gaudy, do the edges look harsh, are there hundreds of trees? To mix elements of more than one setting, you can put the images in a document and make notes such as “this roof, but that balcony and a bluer colour”. Create a collage or bring out the sketchbook.

“Tear images out of home magazines or catalogs and put them on your vision board. You can also draw floorplans, which can help when you’re trying to navigate your character” – Charlotte Dixon

As mentioned by Charlotte Dixon, maps and floor plans are also a handy tool. If a character spends a lot of time in a building, you need to know the layout so they don’t come from the kitchen into the dining room one time and from the ballroom another.

Likewise, if they travel a lot or go outside to a certain place frequently, maps will help keep you orientated. Draw the street of your character’s favourite coffee shop; what will they see as they sip on their routine morning hot beverage?

Maps and floorplans can be drawn by hand on plain, lined or grid paper, or done in excel by changing the cell sizes to square. Grid is particularly useful for smaller buildings. It may not matter if your castle is 100 or 110 metres long, but there’s a big difference if a house is 10 or 20 metres.

For smaller buildings, also make sure that it is reasonable to fit all the furniture you describe in a single room. If you want to go the extra mile, there are also free 3D modelling programs such as Sketch Up, but generally simple 2D maps are enough.

You may also want to create a setting arc if it undergoes a serious change in the story. This would likely be either physical damage or a change in emotion or meaning. For the former, make notes of what is damaged, how it is damaged and the differences (such as being able to see through a hole in a wall).

Conversely, perhaps a damaged place was fixed or renovated. If the emotions connected to a place change, pick out the details. A sagging roof that once may have seemed a sign of degradation could simply add character.

***

Choose the Shape and Style of Narration

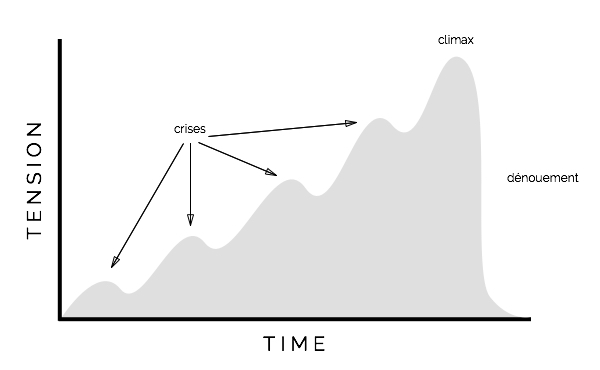

There are three narration shapes your plot can take: linear, non-linear and circular.

Linear narration is when the novel progresses in the typical chronological order. For example, Little Red leaves her house, meets the Wolf in the forest and then again in Grandma’s house.

Non-linear narration shakes things up a bit. In the case of Little Red Riding Hood, for example, Little Red meets the Wolf at Grandma’s, recalls meeting him earlier, is saved by the woodsman, recalls her mum telling her to be careful, and so on, backwards and forwards. Two well-known non-linear novels to have a look at are Catch-22 by Joseph Heller and The Time Traveler’s Wife by Audrey Niffenegger.

Circular narration starts and ends with the characters in the same place. This “place” can refer to a number of things such as a geographical location, an emotional or mental state, or a hierarchical position.

Whatever “place” means for the beginning and end, it should also be important in the middle. The novel The Chrysalids by John Wyndham starts with telepathic mutants being shunned by normal society. They attempt to create a safe place for themselves. However, when they find a whole town of telepaths, they’re looked down on again because of the weakness of their mutation.

If your novel is to be in a nonlinear or circular shape, it’s best to first craft your outline in a linear form. This makes it easier for you as the author to keep track of the story and helps prevent the plot from becoming confused and lost within itself.

“If you’re timebending or rewinding or flashbacking or Groundhog-daying or getting surreal or showing a series of vignettes that add up to a whole or chopping around like the film Memento, you the writer need to know what the simple order is” – Roz Morris

***

If you are enjoying this post and finding it useful, then don’t forget to check back tomorrow for the next instalment…

You can find the previous part here: