So, now we’ve come to the end of our Writer’s Blog Short Story Week, you may be thinking of composing a short story of your own. But how exactly do you go about doing so? To help you out, here is a basic ‘How To’ guide for anyone considering turning their talents to the wonderful genre of the short story.

1. Know what a short story is

Before diving into any genre, it is important to understand the basics of that genre. Most definitions of a short story focus on the following key points:

- A short story is a prose narrative

- Is shorter than a novel

- Deals with limited characters

- Aims to create a single effect

Other definitions, however, are more concerned with word count, stating that a short story may range anywhere between 1,000 – 30,000 words. Anything over 30,000 words, however, tends to be considered ‘too long’, and crosses into the classification of a novella.

But how important are word counts? Well, if you are looking to have your work published, the word count can be extremely important. For instance, most literary magazines prefer their short story entries to be kept brief, and even stipulate a limit for all their submissions. You should always check the submission guidelines of any magazine you wish to send your work to. These guidelines can generally be found on the magazine’s website.

It is also crucial that you never underestimate the importance of reading. Read the form you hope to write in. To see a list of Classic short stories you could check out yesterday’s post.

2. Develop an Idea

Once you know a bit about the genre, and what is expected from a short story, you can begin creating one of your own. As with any fiction writing, this all begins with an idea. But where does a writer find ideas? When faced with this, very question, Neil Gaiman stated:

“You get ideas from daydreaming… You get ideas from asking yourself simple questions. The most important of the questions is just, What if…?”

With this answer, Gaiman highlights the importance of the writer’s imagination in the process of developing a story. But what if your imagination needs a little prompting? Although daydreaming can be an excellent tool in crafting a story, sometimes our imaginations need a little external stimulus to help light the spark. So what sort of external stimulus can be helpful in sparking a good short story idea?

Hint: Eavesdropping

Polite society will tell us it is wrong to listen in on other people’s conversations, but a sly bit of eavesdropping every now and then can be quite invaluable for a writer.

The people in the world around us – whether they be on a train to the city, on the phone in the supermarket, or enjoying a family barbeque in the park – provide an exceptional case study of human character and behaviour. By acting as an observer of daily life, and fusing together what we see and hear with our own imaginations, we can come up with all sorts of story ideas we may otherwise have never considered.

An example of this practice can be seen in ‘Rest Stop’; a short story by Stephen King, published in his collection, ‘Just After Sunset’. This story follows the experience of a writer who stops at a service station to use the bathrooms, only to find himself witness to a case of domestic violence. The writer then faces the tough decision of whether to play hero and intervene, or whether to save himself from a possible beating of his own, hop back in his car, and drive away.

In the notes provided by Stephen King in the back of the book, he admits to this idea sparking from an experience of his own, in which he stopped at a rest stop and overheard a couple engaged in a very heated argument. King writes:

“They both sounded tight and on the verge of getting physical. I wondered what in the world I’d do if that happened…”

In other words, King started with an overheard conversation (or, in this case, argument), then used his imagination to ask himself ‘What if…?’ – ‘What if the argument developed into a physical fight? What would a writer, much like myself, do in this situation?’. ‘Rest Stop’ is therefore an excellent example of how the odd bit of eavesdropping can help fuel our imaginations, and allow us to create an engaging short story.

Hint: Use a memory/experience of your own

‘Rest Stop’ is also a good example of how we can use our own experiences/memories as a starting point for a short story. Possibly the greatest advantage of this technique is the degree of tangibility it lends to our work.

For example, in ‘Rest Stop’, King is able to create a detailed description of the setting by providing a strong vision of the missing children posters, tacked up all over the walls. This attention to finer detail, pulled from King’s own memory, allows the reader to feel as though they are seeing the service station for themselves. It is more realistic, more tangible, more believable.

Of course, any fictional setting/event can be made to feel this way with the inclusion of finer detail, but starting with a memory is great practice. Once you can describe how something looked, felt, smelt, sounded or tasted in your own experience, the better you will be able to describe the fictional experiences of your characters. Try searching your mind for a very clear memory of your own. What did you see? What did you feel? What did you smell? Now use this memory to construct a short story by throwing in the ‘What if?’ question. For example, ‘What if this character had a similar experience?’

Hint: Read the daily papers

They say fact is stranger than fiction, and in no place is this more evident than in the daily news. Like eavesdropping, newspapers and news reports can also provide writers with an interesting case study of real life. Try collecting some news clippings of extraordinary stories, and imagine a character of your own witnessing these events. How does it affect them? How are they involved? Does their experience challenge what was reported in the clipping? Perhaps experiment with different points of view – try writing the story from the varying perspectives of those involved.

Hint: Make a playlist

Another excellent prompt for the imagination is music. For example, try listening to a random song on your ipod. What mood does the song create? What images come to mind? What story do the lyrics tell? Now try writing a story around one or more of these elements.

Hint: General writing prompts

If none of these techniques seem appealing to you, the Internet is full of writing prompts that may ignite your creativity. For example, a list of writing prompts may be found at Writer’s Digest, and Creative Writing Now.

3. Experiment

Sometimes just playing around with ideas can actually lead to some of our best work. Before writing your story, try composing a few ‘test’ paragraphs. Use these paragraphs to trial a number of different voices, styles and points of view (POV). Try writing in first person, then try writing in third person, or possibly even second person (although be wary that second person narratives are rare, and difficult to do well). Experiment with different tenses. Change things around and try to find the style, voice, POV, and so on, best suited for the story you wish to create. For more on finding the right tense/POV/etc for your story, try here.

Another great way to experiment is to try free-writing. Free-writing, much like stream of consciousness, is high speed, continuous writing, free from planning or self-editing/censorship. This type of writing can unlock phrases and ideas, hidden away in our subconscious, that may otherwise prove elusive due to our tendency to over-think.

4. Plan

Despite the previous point about overthinking, there is also something to be said about the benefits of planning. Once you have a solid idea for your work, it is a good idea to plan your story. Although some writers work better with plans than others, mapping out and structuring your ideas can be a highly beneficial process. American novelist, John Gardner once wrote:

“Writing a novel is like heading out over the open sea in a small boat. If you have a plan and a course laid out, that’s helpful.”

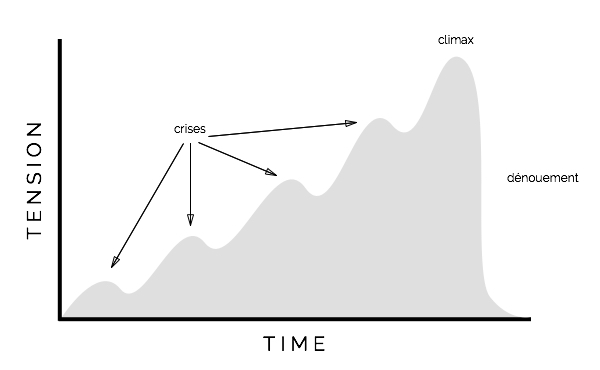

Although short stories may not seem as epic an expedition as a novel, the overall structure of the genres are not so different. Like the novel, a short story is a form of prose narrative, expected to contain a beginning, middle and end. Thus, just as it is helpful to plan a novel, it is also helpful to plan a short story.

Essentially, what a plan does is provide us with a ‘print preview’ of our work. It allows us to see clearly any kinks or problems we may need to smooth over before we commit our story to its final form. (For more on the benefits of planning, read this Writer’s Edit’s article on How To Plan Your Book.) You can plan in whatever way is most helpful to you – whether this be mind-mapping, jotting down your key plot points, writing character profiles, or mapping out the order of events. You may also want to try planning your story using Freytag’s Five Stage Story Structure as a guide.

5. Know the Specifics

If you are composing your short story with the hope of publishing, it is important to take care of the finer details. For instance, who are you writing for? Some writers set out to write a short story with a particular magazine or publication already in mind. However, it is often best not to write this way, unless you have already been commissioned to do so. Writing with a sole publication in mind could not only restrict/limit your story, but could also be potentially devastating if the publication in question decides not to publish. Instead, it is often far better to write the story that feels right for you, then search for magazines that suit the tone/feel of your work, rather than the other way around. In other words, be true to yourself, write what you’re passionate about, and eventually, you and your story will find the right home.

Nevertheless, it is important to demonstrate to any magazine you submit to that you are familiar with their publication, and their style. Before you submit anywhere, ensure you subscribe to the publication, or at least thoroughly read a number of past editions. Make sure that your story suits the publication, and be ready to convince the editors exactly why your story would be suited to their magazine.

But knowing who you’re writing for is about more than knowing the magazines you approach. It is also about knowing your audience. What genre does your story fall under? What themes/issues does it deal with? Once you know who your story will appeal to, you will be better equipped to find that ‘home’ your story is looking for. For example, if your protagonist is a teenager, and your story explores issues of coming of age/crossing the threshold into adulthood, chances are your story falls under ‘young adult fiction’. You should therefore direct your story to a magazine with a largely young adult readership. If, however, your young protagonist happens to be a skilled wizard/dragon-rider, fighting a war against evil goblins, your story’s ultimate genre is likely fantasy, and you may be better off researching which publications appeal most to fantasy readers.

Identifying your target audience, and finding ways to direct your work towards them will provide your story with the ideal environment and conditions to flourish, so always try to keep them in mind.

6. Write it!

Once you have your idea, you’ve played around with different ways of writing, and you have a clear plan for your plot/structure, you can begin to write. Often getting started is the hardest step, so try not to put this off for too long. If you need help, refer to your plan or use some of your experiments as a starting point. Remember, you can always redraft and/or edit later if you are not happy with anything you put down. The most important thing is to get started, and the rest will follow.

7. Don’t Rush

One of the biggest mistakes writers can make is to become so focussed on the end game of getting published, that they don’t take the time to perfect what they’re writing. Often the result of this is an obvious sloppiness to the work, possible plot-holes, contradictions, inconsistences, and an overall rushed feeling that doesn’t do justice to the story being told. So take your time. Don’t rush. If you want to get your story out there, create yourself a writing habit.

Set aside time each day that is purely for writing. To maximise your productivity, limit your distractions during this time. Shut off Facebook, find a room with no television (or a quiet spot outdoors), switch your phone to silent, and just get as much writing done as you possibly can. By making this a regular habit, you can afford your writing the time and focus it deserves.

8. Edit

Once you have a completely finished draft on your hands, you can begin to edit. Editing is an extremely crucial process that allows us to mould our work into its best, possible shape. It is through editing that we ensure our writing is as effective as possible. For any writer, the first step to editing is to edit your own work, however, when editing your work, it is also important to consider the feedback of others. Try taking your story along to a writing group. Writing groups are a great place to seek constructive feedback from other writers. This feedback, along with the workshop nature of these groups, can prove absolutely invaluable when revising your work. During the editing process, it is also highly beneficial to consult the advice of a beta reader. A beta reader can serve as a proof-reader, check the story for effectiveness, plot-holes, consistency, believability, and so on. If you do not already know an ideal beta reader, writing groups are a great place to meet them, so get out there!

Once you have edited, re-edited, and edited some more, you should finally find your story is in a form you are happy to call ‘finished’. Now you’re ready to try submitting your work to the magazines/publications you have properly researched as suitable for your story. This can be a daunting task, and you may well face a number of knock-backs, but if you persevere, you will eventually find that you have a published copy of your short story, right there in front of you, and for all to see.

Happy writing!