“Remember when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.” – Neil Gaiman

Blog posts, articles, pictures, thoughts and quotes…

“Remember when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.” – Neil Gaiman

One Friday in 2012, Christie’s New York auctioned a copy of John James Audubon’s Birds of America, which already holds the title of most valuable printed book in the world, having sold for about $11.5 million in 2010. In fact, according to The Economist, a true list of the ten most valuable single books ever sold would have to include five copies of The Birds of America. Though that sale didn’t break the record, the book still sold for a considerable sum: $7.9 million.

To help you brush up on your knowledge of the very old and very valuable, here is a list of the ten most expensive books ever sold – no white gloves necessary. Look through the overview, and then head upstairs to check your attics for any forgotten dusty tomes – you could be a millionaire and not even know it.

Originally printed in 1794, The First Book of Urizen is one of the major pieces (and some say the most important) in Blake’s series of prophetic works. One of only eight known surviving copies was sold at Sotheby’s New York in 1999 for $2.5 million to a private collector.

Before this book, meant to be the same children’s book that figures heavily in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, became a mass-market paperback, J.K. Rowling created seven original copies, each one handwritten and illustrated by Rowling herself. Six were given to friends and editors, but in 2007, one of the seven was put up for auction. It was snapped up by Amazon.com for a whopping $3.98 million, making it the most expensive modern manuscript ever purchased at auction. The money from the sale of the book was donated to The Children’s Voice charity campaign.

The world’s first printed atlas, and the world’s first book to make use of engraved illustrations, Ptolemy’s 1477 Cosmographia sold at Sotheby’s London in 2006 for £2,136,000, or almost $4 million at the time.

Definitely the most expensive book ever written about fruit trees (featuring sixteen different varieties!), a copy of this lush, five volume set of illustrations and text sold for about $4.5 million in 2006.

A copy of the Gutenberg Bible sold in 1987 for a then-record $4.9 million at Christie’s New York. Only 48 of the books — the first to be printed with movable type — exist in the world.

Though the First Folio’s original price was a single pound (one or two more if you wanted it bound in leather or otherwise adorned), intact copies are now among the most highly prized finds among book collectors, with only an estimated 228 (out of an original 750) left in existence. In 2001, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen purchased a copy for $6,166,000 at Christie’s New York.

A first edition of the 15th century bawd-fest sold for £4.6m (or about $7.5 million at the time) at Christie’s in London in 1998. Of the dozen known copies of the 1477 first edition, this was the last to be held privately, and was originally purchased for £6 by the first Earl Fitzwilliam at the sale of John Radcliffe’s library at Christie’s in 1776. Talk about growing your investment.

In 2000, Christie’s auctioned off a copy (one of only 119 known complete copies in the world) of Birds in America for $8,802,500. Ten years later, another complete first edition was sold at London at Sotheby’s for £7,321,250 (or about $11.5 million) In 2012, another copy of the enormous four volume went up for auction at Christie’s, and sold for a considerable $7.9 million.

Originally commissioned by Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony, for the altar of the Virgin Mary at the Brunswick Cathedral, this gospel book was purchased by the German government at Sotheby’s of London in 1983 for £8,140,000, or about $11.7 million (at the time). At 266 pages, including 50 full-page illustrations, the book is considered a masterpiece of the 12th century Romanesque illuminated manuscript.

The most famous of da Vinci’s scientific journals, the 72-page notebook is filled with the great thinker’s handwritten musings and theories on everything from fossils to the movement of water to what makes the moon glow. The manuscript was first purchased in 1717 by Thomas Coke, who later became the Earl of Leicester, and then, in 1980, bought from the Leicester estate by art collector Armand Hammer (whose name the manuscript bore for the fourteen years he owned it). In 1994, Bill Gates nabbed the journal at auction for $30,800,000, making it the most expensive book ever purchased. But hey, at least Gates put his purchase to good use — he had the book scanned and turned into a screensaver distributed with Microsoft Plus! for Windows 95.

***

So next time you are cleaning out the loft and you come across a dusty old book, check how much it’s worth before you condemn it to the scrap heap. It might be worth a fortune!

Via: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/the-10-most-expensive-books-in-the-world/

The word “bibliophile” literally means a lover (phile) of books (biblio). The term is often thrown around to refer to people who simply like to read, but in its most precise interpretation, “bibliophile” means something more specific: someone who loves books particularly how they look, how they smell, what they feel like. Of course, most bibliophiles are great readers, collecting (OK, hoarding) books in part because they love the narratives in them.

But they also value books as fascinating objects in themselves, objects with their own stories to tell. These are readers who will never really be satisfied with electronic books – how can a cold iPad screen possibly compare to a tattered, musty, well-loved print book? To find out if you are one of those blessed with (or suffering from, depending on you point of view) bibliophilia, read on.

Certain books, ones I’ve read over and over since I was a teenager, have enormous personal value to me. Of course, I want to share these wonderful, formative reading experiences with other people. But other people are jerks sometimes! What if I lend a friend a book and she dog-ears the pages? What if she breaks the spine? WHAT IF SHE LOSES IT? So I have my copy, and a loaner copy, and everyone is happy. All perfectly normal, right?

Oh, come on. We all do it. Actually, I don’t judge people so much by what books they have as by whether they own books or not. I don’t care what people read, but someone who doesn’t have any books is probably an orc and cannot be trusted.

My books are organized according to an intricate system that is so logical that only I can understand it. Some are alphabetized, some are categorized according to genre, some are ordered by colour. You know what I’m talking about, right?

Used books are the best: they’re cheap, they hold the same texts as newer editions, and sometimes you find amazing evidence of past readers – marginal notes, bookmarks, inscriptions. All tiny glimpses into other people’s lives. Bibliophiles can’t get enough of all of that. More, please.

Because they are pretty. Spaces always look more interesting, more inviting, and more homey when they are filled with books.

For bibliophiles, books form a major part of one’s personal identity. It’s only natural that you’d want to be surrounded by them on your big day.

Preferably one with a ladder. And yes, you’re going to swing around the room, gesturing grandly, whatever.

I’ve gone far, far out of my way to visit places like Haworth (home of the Brontë family in West Yorkshire) and Prince Edward Island (home Lucy Maud Montgomery and the Anne books). There is something powerful in seeing where my favourite books were written, and in seeing great authors’ own books. Because, naturally, great writers tend to be bibliophiles themselves.

I have at least four copies of Pride and Prejudice, including a battered paperback edition, a fancy leather-bound edition, a critical edition, and an illustrated edition. And they are all completely necessary to my life.

One would have to have crazy amounts of money in order to fulfill this criterion, but I think we can assume that whoever spent $11.5 million on a copy of John James Audubon’s Birds of America is a pretty hard-core book lover.

***

“One can never be alone enough to write,” Susan Sontag observed.

Solitude, in fact, seems central to many great writers’ daily routines — so much so, it appears, that part of the writer’s curse might be the ineffable struggle to submit to the spell of solitude and escape the grip of loneliness at the same time.

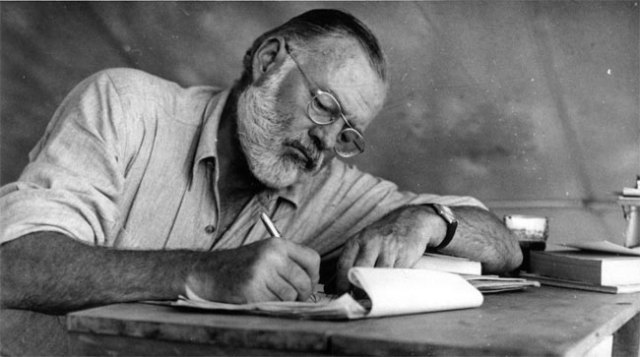

In October of 1954, Ernest Hemingway was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. But he didn’t exactly live every writer’s dream: First, he told the press that Carl Sandburg, Isak Dinesen and Bernard Berenson were far more worthy of the honour, but he could use the prize money; then, depressed and recovering from two consecutive plane crashes that had nearly killed him, he decided against traveling to Sweden altogether.

Choosing not to attend the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm on December 10, 1954, Hemingway asked John C. Cabot, the United States Ambassador to Sweden at the time, to read his Nobel acceptance speech, found in the 1972 biography Hemingway: The Writer as Artist. At a later date, Hemingway recorded the speech in his own voice. Here is the transcript of that speech:

Having no facility for speech-making and no command of oratory nor any domination of rhetoric, I wish to thank the administrators of the generosity of Alfred Nobel for this Prize.

No writer who knows the great writers who did not receive the Prize can accept it other than with humility. There is no need to list these writers. Everyone here may make his own list according to his knowledge and his conscience.

It would be impossible for me to ask the Ambassador of my country to read a speech in which a writer said all of the things which are in his heart. Things may not be immediately discernible in what a man writes, and in this sometimes he is fortunate; but eventually they are quite clear and by these and the degree of alchemy that he possesses he will endure or be forgotten.

Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.

For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment. He should always try for something that has never been done or that others have tried and failed. Then sometimes, with great luck, he will succeed.

How simple the writing of literature would be if it were only necessary to write in another way what has been well written. It is because we have had such great writers in the past that a writer is driven far out past where he can go, out to where no one can help him.

I have spoken too long for a writer. A writer should write what he has to say and not speak it. Again I thank you.

***

Via: https://www.brainpickings.org/ernest-hemingway-1954-nobel-speech/

“Stay faithful to the stories in your head” – Paula Hawkins

How many people die with their best work still inside them?

We often assume that great things are done by those who were blessed with natural talent, genius, and skill.

But how many great things could have been done by people who never fully realized their potential?

I think many of us, myself included, are capable of much more than we typically produce — our best work is often still hiding inside of us.

How can you pull that potential out of yourself and share it with the world?

Perhaps the best way to develop better daily routines.

When you look at the top performers in any field, you see something that goes much deeper than intelligence or skill.

They possess an incredible willingness to do the work that needs to be done. They are masters of their daily routines.

As an example of what separates successful people from the rest of the pack, take a look at some of the daily routines of famous writers from past and present.

In an interview with The Paris Review, E.B. White, the famous author of Charlotte’s Web, talked about his daily writing routine…

I never listen to music when I’m working. I haven’t that kind of attentiveness, and I wouldn’t like it at all. On the other hand, I’m able to work fairly well among ordinary distractions. My house has a living room that is at the core of everything that goes on: it is a passageway to the cellar, to the kitchen, to the closet where the phone lives. There’s a lot of traffic. But it’s a bright, cheerful room, and I often use it as a room to write in, despite the carnival that is going on all around me.

In consequence, the members of my household never pay the slightest attention to my being a writing man — they make all the noise and fuss they want to. If I get sick of it, I have places I can go. A writer who waits for ideal conditions under which to work will die without putting a word on paper.

In a 2004 interview, Murakami discussed his physical and mental habits…

When I’m in writing mode for a novel, I get up at four a.m. and work for five to six hours. In the afternoon, I run for ten kilometers or swim for fifteen hundred meters (or do both), then I read a bit and listen to some music. I go to bed at nine p.m.

I keep to this routine every day without variation. The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.

But to hold to such repetition for so long — six months to a year — requires a good amount of mental and physical strength. In that sense, writing a long novel is like survival training. Physical strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity.

In an interview with George Plimpton, Hemingway revealed his daily routine…

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write. You read what you have written and, as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go on from there.

You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again. You have started at six in the morning, say, and may go on until noon or be through before that.

When you stop you are empty, and at the same time never empty but filling, as when you have made love to someone you love. Nothing can hurt you, nothing can happen, nothing means anything until the next day when you do it again. It is the wait until the next day that is hard to get through.

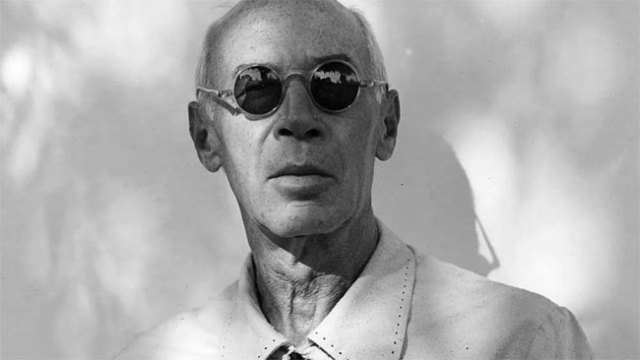

In 1932, the famous writer and painter, Henry Miller, created a work schedule that listed his “Commandments” for him to follow as part of his daily routine. This list was published in the book, Henry Miller on Writing.

Work on one thing at a time until finished. Start no more new books, add no more new material to “Black Spring.” Don’t be nervous. Work calmly, joyously, recklessly on whatever is in hand. Work according to Program and not according to mood. Stop at the appointed time! When you can’t create you can work. Cement a little every day, rather than add new fertilizers. Keep human! See people, go places, drink if you feel like it. Don’t be a draught-horse! Work with pleasure only. Discard the Program when you feel like it — but go back to it next day. Concentrate. Narrow down. Exclude. Forget the books you want to write. Think only of the book you are writing. Write first and always. Painting, music, friends, cinema, all these come afterwards.

In 1965, Vonnegut wrote a letter to his wife Jane about his daily writing habits, which was published in the recent book: Kurt Vonnegut: Letters.

I awake at 5:30, work until 8:00, eat breakfast at home, work until 10:00, walk a few blocks into town, do errands, go to the nearby municipal swimming pool, which I have all to myself, and swim for half an hour, return home at 11:45, read the mail, eat lunch at noon.

In the afternoon I do schoolwork, either teach or prepare. When I get home from school at about 5:30, I numb my twanging intellect with several belts of Scotch and water ($5.00/fifth at the State Liquor store, the only liquor store in town. There are loads of bars, though.), cook supper, read and listen to jazz (lots of good music on the radio here), slip off to sleep at ten. I do push ups and sit ups all the time, and feel as though I am getting lean and sinewy, but maybe not.

The last seven books Jodi Picoult has written have all hit number 1 on the New York Times bestseller list. In an interview with Noah Charney, she talks about her approach to writing and creating…

I don’t believe in writer’s block. Think about it — when you were blocked in college and had to write a paper, didn’t it always manage to fix itself the night before the paper was due? Writer’s block is having too much time on your hands. If you have a limited amount of time to write, you just sit down and do it. You might not write well every day, but you can always edit a bad page. You can’t edit a blank page.

In a 2013 interview with The Daily Beast, the American author and poet discussed her writing career and her daily work habits…

I keep a hotel room in my hometown and pay for it by the month.

I go around 6:30 in the morning. I have a bedroom, with a bed, a table, and a bath. I have Roget’s Thesaurus, a dictionary, and the Bible. Usually a deck of cards and some crossword puzzles. Something to occupy my little mind.

I think my grandmother taught me that. She didn’t mean to, but she used to talk about her “little mind.” So when I was young, from the time I was about 3 until 13, I decided that there was a Big Mind and a Little Mind. And the Big Mind would allow you to consider deep thoughts, but the Little Mind would occupy you, so you could not be distracted. It would work crossword puzzles or play Solitaire, while the Big Mind would delve deep into the subjects I wanted to write about.

I have all the paintings and any decoration taken out of the room. I ask the management and housekeeping not to enter the room, just in case I’ve thrown a piece of paper on the floor, I don’t want it discarded. About every two months I get a note slipped under the door: “Dear Ms. Angelou, please let us change the linen. We think it may be moldy!”

But I’ve never slept there, I’m usually out of there by 2. And then I go home and I read what I’ve written that morning, and I try to edit then. Clean it up.

Easy reading is damn hard writing. But if it’s right, it’s easy. It’s the other way round, too. If it’s slovenly written, then it’s hard to read. It doesn’t give the reader what the careful writer can give the reader.

The Pulitzer Prize nominee has written over a dozen books, the last nine of which have all made the New York Times bestseller list. During a 2012 interview, she talked about her daily routine as a writer and a mother…

I tend to wake up very early. Too early. Four o’clock is standard. My morning begins with trying not to get up before the sun rises. But when I do, it’s because my head is too full of words, and I just need to get to my desk and start dumping them into a file. I always wake with sentences pouring into my head.

So getting to my desk every day feels like a long emergency. It’s a funny thing: people often ask how I discipline myself to write. I can’t begin to understand the question. For me, the discipline is turning off the computer and leaving my desk to do something else.

I write a lot of material that I know I’ll throw away. It’s just part of the process. I have to write hundreds of pages before I get to page one.

For the whole of my career as a novelist, I have also been a mother. I was offered my first book contract, for The Bean Trees, the day I came home from the hospital with my first child. So I became a novelist and mother on the same day. Those two important lives have always been one for me. I’ve always had to do both at the same time.

So my writing hours were always constrained by the logistics of having my children in someone else’s care. When they were little, that was difficult. I cherished every hour at my desk as a kind of prize. As time has gone by and my children entered school it became progressively easier to be a working mother.

My oldest is an adult, and my youngest is 16, so both are now self-sufficient — but that’s been a gradual process. For me, writing time has always been precious, something I wait for and am eager for and make the best use of. That’s probably why I get up so early and have writing time in the quiet dawn hours, when no one needs me.

I used to say that the school bus is my muse. When it pulled out of the driveway and left me without anyone to take care of, that was the moment my writing day began, and it ended when the school bus came back. As a working mother, my working time was constrained.

On the other hand, I’m immensely grateful to my family for normalizing my life, for making it a requirement that I end my day at some point and go and make dinner. That’s a healthy thing, to set work aside and make dinner and eat it. It’s healthy to have these people in my life who help me to carry on a civilized routine. And also to have these people in my life who connect me to the wider world and the future.

My children have taught me everything about life and about the kind of person I want to be in the world. They anchor me to the future in a concrete way. Being a mother has made me a better writer. It’s also true to say that being a writer has made me a better mother.

Englander is an award-winning short story writer, and in this interview he talks about his quest to eliminate all distractions from his writing routine …

Turn off your cell phone. Honestly, if you want to get work done, you’ve got to learn to unplug. No texting, no email, no Facebook, no Instagram. Whatever it is you’re doing, it needs to stop while you write. A lot of the time (and this is fully goofy to admit), I’ll write with earplugs in — even if it’s dead silent at home.

Russell has only written one book … and it was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. In an interview with The Daily Beast, she talks about her daily struggle to overcome distraction and write …

I know many writers who try to hit a set word count every day, but for me, time spent inside a fictional world tends to be a better measure of a productive writing day. I think I’m fairly generative as a writer, I can produce a lot of words, but volume is not the best metric for me.

It’s more a question of, did I write for four or five hours of focused time, when I did not leave my desk, didn’t find some distraction to take me out of the world of the story? Was I able to stay put and commit to putting words down on the page, without deciding mid-sentence that it’s more important to check my email, or “research” some question online, or clean out the science fair projects in the back for my freezer?

I’ve decided that the trick is just to keep after it for several hours, regardless of your own vacillating assessment of how the writing is going. Showing up and staying present is a good writing day.

I think it’s bad so much of the time. The periods where writing feels effortless and intuitive are, for me, as I keep lamenting, rare. But I think that’s probably the common ratio of joy to despair for most writers, and I definitely think that if you can make peace with the fact that you will likely have to throw out 90 percent of your first draft, then you can relax and even almost enjoy “writing badly.”

In an interview for the series How I Write, Jacobs talks about his daily writing routines and dishes out some advice for young writers …

My kids wake me up. I have coffee. I make my kids breakfast, take them to school, then come home and try to write. I fail at that until I force myself to turn off my Internet access so I can get a little shelter from the information storm.

I am a big fan of outlining. I write an outline. Then a slightly more detailed outline. Then another with even more detail. Sentences form, punctuation is added, and eventually it all turns into a book.

I write while walking on a treadmill. I started this practice when I was working on Drop Dead Healthy, and read all these studies about the dangers of the sedentary life. Sitting is alarmingly bad for you. One doctor told me that “sitting is the new smoking.” So I bought a treadmill and put my computer on top of it. It took me about 1,200 miles to write my book. I kind of love it — it keeps me awake, for one thing.

Jacobs has advice for young writers, too…

Force yourself to generate dozens of ideas. A lot of those ideas will be terrible. Most of them, in fact. But there will be some sparkling gems in there too. Try to set aside 20 minutes a day just for brainstorming.

In an interview with Noah Charney, Housseni talks about his daily writing habits and the essential things that all writers have to do …

I don’t outline at all, I don’t find it useful, and I don’t like the way it boxes me in. I like the element of surprise and spontaneity, of letting the story find its own way.

For this reason, I find that writing a first draft is very difficult and laborious. It is also often quite disappointing. It hardly ever turns out to be what I thought it was, and it usually falls quite short of the ideal I held in my mind when I began writing it.

I love to rewrite, however. A first draft is really just a sketch on which I add layer and dimension and shade and nuance and colour. Writing for me is largely about rewriting. It is during this process that I discover hidden meanings, connections, and possibilities that I missed the first time around. In rewriting, I hope to see the story getting closer to what my original hopes for it were.

I have met so many people who say they’ve got a book in them, but they’ve never written a word. To be a writer — this may seem trite, I realize — you have to actually write. You have to write every day, and you have to write whether you feel like it or not.

Perhaps most importantly, write for an audience of one — yourself. Write the story you need to tell and want to read. It’s impossible to know what others want so don’t waste time trying to guess. Just write about the things that get under your skin and keep you up at night.

These daily routines work well for writing, but their lessons can be applied to almost any goal you hope to achieve.

For example …

1. Pushing yourself physically prepares you to work hard mentally. Vonnegut did pushups as a break from writing. Murakami runs 10 kilometers each day. A.J. Jacobs types while walking on a treadmill. You can decide what works for you, but make sure you get out and move.

2. Do the most important thing first. Notice how many excellent writers start writing in the morning? That’s no coincidence. They work on their goals before the rest of the day gets out of control. They aren’t wondering when they’re going to write and they aren’t battling to “fit it in” amongst their daily activities because they are doing the most important thing first.

3. Embrace the struggle and do hard work. Did you see how many writers mentioned their struggle to write? Housseni said that his first drafts are “difficult” and “laborious” and “disappointing.” Russell called her writing “bad.” Kingsolver throws out a hundred pages before she gets to the first page of a book.

What looks like failure in the beginning is often the foundation of success. You have to grind out the hard work before you can enjoy your best work.

Happy writing! 🙂

***

http://www.businessinsider.com/the-daily-routines-of-12-famous-writers

Everyone has their quirks, even famous authors. But here are 13 fun facts about them that you probably didn’t know, and might make you see them differently.

1. Dan Brown, the famed author of Da Vinci Code, was previously a pop singer and had once written a song about phone sex.

2. The author of Famous Five and Secret Seven Series, Enid Blyton, hated kids and got hopping mad whenever children made a racket in her neighborhood. Even her younger daughter Imogen called her, “arrogant, insecure, pretentious and without a trace of maternal instinct.”

3. The accomplished horror writer Stephen King has triskaidekaphobia, irrational fear of number 13. He’s so terrified of it that he wouldn’t pause reading or writing if he’s on page 13 or it’s multiples till he reaches a safe number.

4. Apart from being an adept author, Mark Twain was also the inventor of the self-pasting scrapbook and the elastic-clasp brassiere strap.

5. Lewis Carroll allegedly proposed to the real 11-year-old Alice and was also thought to be a “heavily repressed pedophile”.

6. Charles Dickens was so fascinated with dead bodies that he’d spend most of his time at the Paris Morgue.

7. On May 16, 1836, Edgar Allan Poe married his first cousin Virginia Eliza Clemm. He was 26 at that time, and she was 13.

8. William S. Burroughs, the author of Naked Lunch, shot his wife in the head during a drunken attempt at playing William Tell. The controversial beat writer had also once chopped the top joint of his finger to gift his ex-boyfriend but instead presented it to his psychiatrist, who freaked out and committed him to a private clinic.

9. Two young school girls tricked Sherlock Holmes’s author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle into believing in the existence of fairies.

10. Jonathan Swift, the creator of Gulliver’s Travels, was first to coin the name Vanessa.

11. Alexandre Dumas‘s pants fell off during his first duel at age 23.

12. J.R.R Tolkien was known to be a wacky prankster who once dressed as an ax-wielding Anglo-Saxon warrior and chased his neighbor.

13. Maya Angelou once worked as a sex worker and a ‘madam’, and chronicled her experiences in her memoir Gather Together in My Name.

***

What’s burning inside of you?

Light that fire!

Happy writing x

Image via Pixabay

Writing character deaths is a tricky task that many writers grapple with. Due to the huge prevalence of death in fiction, it has increasingly become a theme writers feel they have to include.

Most notably, literature that gets showered in accolades often includes the tragic deaths of all manner of loveable characters. Parental figures, faithful pets and best friends are the most common victims.

Awards given to books aimed at younger audiences, such as the Newbery Medal and Michael L. Printz award, often seem to seek out the most poignant, shocking deaths that catapult protagonists into maturity.

Books like Bridge To Terabithia and Looking For Alaska are famed for cutting adolescent romance short with sudden death, while Charlotte’s Web made audiences weep over a dying spider.

Gordon Korman, in No More Dead Dogs, jokes that:

The dog always dies. Go to the library and pick out a book with an award sticker and a dog on the cover. Trust me, that dog is going down.”

All of this begs a few questions. Has death in fiction become a cheap gimmick, included with the sole intention of nabbing awards? Do writers have to include death for their story to have emotional depth?

Whatever the answer to these questions, it’s undeniable that death is a theme with enduring relevance. As long as you take steps to ensure character deaths are written with care, with the grand scheme of your narrative always in mind, its presence in your writing won’t be cheap.

Here are a few pointers for dealing with death in your fiction.

An important step in understanding death in fiction is pondering its significance to audiences, and considering why it’s one of the most frequently portrayed themes. Human mortality has been reflected upon since the birth of literature, often elevating writing and provoking thought among readers about the nature of life.

Modern writers often see death as a theme of universal value, the ultimate existential dilemma. Without fail, the theme can rouse feelings of anxiety and fear, while also potentially opening up avenues to self-discovery and coming-of-age. Additionally, death has great symbolic importance as part of the natural cycle of birth and decay.

With all this to consider, it’s easy to see why death often wins writers’ awards. But it’s important to be honest with yourself as a writer, and to consider what the idea of death means in the unique context of your story. It’s too metaphysical and powerful a theme to simply shoehorn into a narrative.

This brings us to our next piece of advice: ensuring there are valid reasons for including character deaths in your story.

There are many reasons why death can be important to a story, and many ways it can add depth to situations. Having specific reasons for including death in your story can help you craft significant death scenes effectively.

Let’s take a look at some of the reasons you might incorporate a character death into your story.

The death of characters can seriously raise the stakes. It throws the characters into a state of immediacy, where danger is imminent and the audience becomes quickly invested due to escalating tension.

For example, in the Harry Potter series, the deaths of major mentor figures Sirius Black and Professor Dumbledore signalled the fact that Harry was on his own, left to face an increasingly deadly foe without the safety of his childhood tethers.

Incorporating death can also create an atmosphere of dread and mystery. In some instances, it can clearly communicate the wickedness of an antagonist.

A brief glance at lists of top villains in literature demonstrates how compelling villains often leave a bloody trail in their wake, which adds to their menacing personas – especially when their true identities are not immediately known but the deaths they cause pack a narrative punch.

If grief, guilt, horror and other feelings associated with death are conveyed successfully, the audience will have a strong emotional response. A great way of learning how to create a lasting emotional impression is to look for what others consider great death scenes.

What pulls on heartstrings will always be quite a subjective and varied affair, but steering clear of over-the-top melodrama will be your best bet.

The Guardian‘s article on the greatest death scenes in literature displays that readers and writers alike are captivated by scenes which play on universal human emotions such as desperation, denial and existential fatigue. Other lists of great deaths show how death scenes accompanied by graphic detail can also often trigger a visceral response, especially when paired with the emotional trauma of characters.

Study what you find striking in death scenes. What makes your heart hurt or beat faster? Additionally, look for what you find lacklustre or unconvincing.

Have you ever read a hokey death scene where a parent dies because the author doesn’t know what to do with them, or scenes where crying cancer patients are milked for all their dramatic worth?

Be careful not to venture into the realm of purple prose. Think clearly about what strong feelings you wish to trigger in your audience and learn the art of subtlety.

Death can be a motivating factor for growth or self-discovery. It can even be an impetus for characters to shift their habits and lifestyle, which can pose interesting challenges and drive the story.

In Stephen King’s short story The Body, death has a heavy impact on the coming-of-age of the main character, Gordie. He is unable to properly grapple with his older brother’s death, but finds himself on a quest to find the body of a dead neighbourhood boy – a journey that pushes him into the realm of adulthood as he slowly understands the bleak aspects of life.

A focus on death can also change the way audiences view historical events, and can make us reflect over existential questions.

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki prompted fierce debate over whether the event was justified. John Hersey’s famed non-fiction book Hiroshima took a human interest angle that detailed the graphic death and injuries of bombing victims in stark, factual language.

The book triggered stronger discussion over the horror of the event, the hopelessness of war, and life in the nuclear age.

George R. R. Martin, author of the A Song of Ice and Fire series, is famous for the fact that any one of his characters – no matter how important – can die. He states:

I’ve been killing characters my entire career. Maybe I’m just a bloody-minded bastard, I don’t know, [but] when my characters are in danger, I want you to be afraid to turn the page [and to do that] you need to show right from the beginning that you’re playing for keeps.”

The unpredictability attached to Martin’s character deaths enlivens his stories. But being unpredictable doesn’t mean writing death scenes purely to shock or pull cheaply on heartstrings.

Instead, it means playing with audience expectations, while remaining true to your characterisation and the intent of your overall story.

Think about whether or not there are predictable patterns in your writing, whether you always kill off characters due to aimlessness in your plot, or whether you lean on killing a certain type of character, such as a family member.

Also ponder over the predictability of your prose. Do you lean on cliched phrases and flowery descriptions to get an emotional point across? Perhaps incorporating some of these tips on how to add realistic details to death scenes can make your scenes seem unique and tangible.

Image via Pixabay

One of the greatest joys of reading is not knowing what to expect, and feeling as if the outcome is not only surprising but also credible. Conversely, it can also be satisfying if the plot goes to a place you do expect, but is dealt with in a fresh and interesting way.

Death scenes we do expect can become infinitely more valuable if the aftermath and the way characters react bring us to new places.

For instance, in Donna Tartt’s acclaimed novel The Secret History, the murder of a main character is revealed in the first few sentences. Although we know death is coming, we become enraptured by the well-drawn characterisation of the doomed murderers and the friend they will inevitably kill.

In this way, our expectation of death makes everything that comes before it more engaging, as the author delves into the psychosis of characters and makes us guess what will push them over the edge. This type of emotional tension makes death fresher, as it gains a more foreboding presence.

When the death scene comes, we become gripped with greater emotional tension as we ponder over what will happen next. The initial questions are simple. Will they be caught? How will they talk their way out of this?

What follows is what makes the novel special, as the the author interweaves feelings of intense moral conflict and unexpected grief to prompt characters to behave in erratic and passionate ways.

This effectively demonstrates the full storytelling strength of death as a theme, when it’s used in a way that is both predictable but powerful.

Judges in the writing industry often seek the sorrow and existential angst that death brings. It’s no wonder that many writers gravitate towards this concept, trying to portray it in ways nobody has before.

However, as a writer, it’s important to ask yourself if you’re merely killing a character because you don’t know how else to elevate your story. By including character deaths, are you being true to your vision?

Keep in mind the significance of death scenes, while also learning death-free ways to deal with situations.

Aristotle states that to master the art of tragedy, one must elicit feelings of both horror and pity. These strong feelings don’t always require the presence of death and maudlin depictions of grief.

Lisa Genova’s Still Alice is famously heartbreaking but features no death; instead, feelings of pity and sadness are triggered from something as complex and emotionally challenging as the deterioration of one’s mind, and by extension, sense of self.

The Coen brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis also foregoes death for something that strikes a different, painful chord. It tells the story of a man trapped in overwhelming and constant failure, as he chases his dream of creative success.

The feelings of hopelessness, futility, fear, anxiety, and introspection tackled in these stories are varied and infinitely worth exploring.

***

Remember that tragedy, and any other situation with emotional depth, doesn’t always require a body count. Happy writing!

Via: https://writersedit.com/fiction-writing/effective-ways-deal-character-deaths/

Henry Miller (26 December 1891 – 7 June 1980) was a prolific writer and painter. In 1932-1933, while working on what would become his first published novel, Tropic of Cancer, Miller devised and adhered to a stringent daily routine to propel his writing. Among it was this list of eleven commandments, found in Henry Miller on Writing:

COMMANDMENTS

- Work on one thing at a time until finished.

- Start no more new books, add no more new material to ‘Black Spring.’

- Don’t be nervous. Work calmly, joyously, recklessly on whatever is in hand.

- Work according to Program and not according to mood. Stop at the appointed time!

- When you can’t create you can work.

- Cement a little every day, rather than add new fertilizers.

- Keep human! See people, go places, drink if you feel like it.

- Don’t be a draught-horse! Work with pleasure only.

- Discard the Program when you feel like it—but go back to it next day. Concentrate. Narrow down. Exclude.

- Forget the books you want to write. Think only of the book you are writing.

- Write first and always. Painting, music, friends, cinema, all these come afterwards.

Under a part titled Daily Program, his routine also featured the following wonderful blueprint for productivity, inspiration, and mental health:

MORNINGS:

If groggy, type notes and allocate, as stimulus.If in fine fettle, write.

AFTERNOONS:

Work on section in hand, following plan of section scrupulously. No intrusions, no diversions. Write to finish one section at a time, for good and all.

EVENINGS:

See friends. Read in cafés.

Explore unfamiliar sections — on foot if wet, on bicycle if dry.

Write, if in mood, but only on Minor program.

Paint if empty or tired.

Make Notes. Make Charts, Plans. Make corrections of MS.

Note: Allow sufficient time during daylight to make an occasional visit to museums or an occasional sketch or an occasional bike ride. Sketch in cafés and trains and streets. Cut the movies! Library for references once a week.

Wouldn’t it be great to add a little of his routine to yours, for a bit of daily inspiration!

***