Characterisation is, without doubt, one of the most important elements to master when writing a novel or short story.

You may have dreamed up a plot of unparalleled genius or a storyline so amazing you have your readers drooling. However, if you don’t have authentic and compelling characters driving the story, no one will ever reach the final page.

If a story is a sailboat, characters are the rudder that steers the whole ship.

Clever’s not enough to hold me – I want characters who are more than devices to be moved about for Effect” – Laura Anne Gilman

Characterisation is defined by what the characters think, say and do. It’s about the writer developing the personality of the people in the story to make the work interesting, compelling, and affecting.

One could go so far to say characterisation is even more important than plot. If your character is fascinating, whatever they do will take on gravitas.

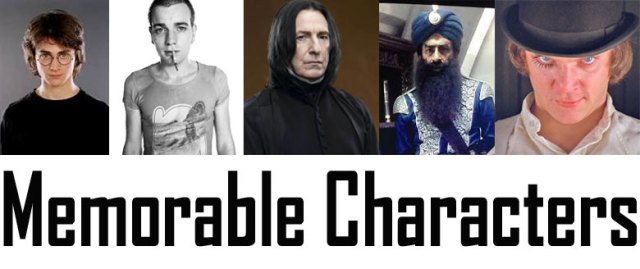

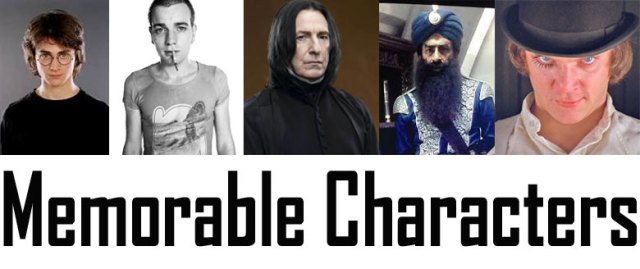

The best characters are the ones that seem to take on a life on their own. For example, when the reader is always drawn back to the book because they can’t help wondering what the character is up to. It’s not as hard as you think to create a character as memorable as Harry Potter or Sherlock Holmes.

Know Your Character

To allow the readers to engage with your characters, they need to become multi-faceted, living, breathing individuals. You have to know them as personally as you know yourself.

The best way to achieve this is by creating a complete character profile that you can always refer to. This way you can trace how a character might react to every situation and how they might feel about the things that happen to them.

Consider these major factors when formulating a character profile:

Develop A Thorough Backstory

For your character to function successfully as a reliable entity, they must possess a past that has shaped who they are when the reader meets them. You don’t have to reveal it all at once, or even reveal it at all. However, it’s important for putting the character’s actions into context. It’s also a very useful way of teasing out information throughout a story by allowing the reader to slowly learn more about the character.

The key influences on a backstory often include:

- Where the character grew up

- Family members

- Past trauma

- Religion

- Socio-economic status

- Job

- School

The backstory will be a major influence on how the character moves through the story.

For example, if your character has a traumatic past, it will often result in an unresolved personal conflict when they are older. As outlined in his biography, Harry Potter’s experiences as a child directly affected him as an adult.

When he was a baby, Harry and his parents were attacked by Lord Voldemort. His parents were killed but Harry miraculously survived. When he was older, he continually came face to face with his nemesis. Over many years he began to learn more about why this happened and why other strange things were happening to him. This resulted in a growing motivation to pursue this knowledge, leading him into greater conflict, not only with Voldemort but other characters, include Professor Snape, the Malfoy’s and Slytherins.

For this reason, he reached out for allies. Since many of his allies didn’t survive, including Harry’s Godfather Sirius Black, Harry became angrier and more emotionally damaged. However, he was able to use the love his parents showed in protecting him as strength to overcome his obstacles.

Examine Your Character’s Personality

To some degree, the backstory shapes a character’s personality. However, the personality is also less concrete. Having a good grasp of your character’s personality will allow you to remain consistent throughout the novel and understand how events will have different impacts.

You might ask yourself whether your character is an introvert or an extrovert? Will they be funny, intelligent, kind, charismatic or cowardly? What part of their personality will you seek to emphasise in order to build a connection between them and the reader? Do they have hobbies that reveal more about their outlook?

You may also consider what kind of attitudes and opinions your characters have about life that make them intriguing. For example Mark Renton in Trainspotting, by Irvine Welsh, is a black-humoured heroin addict. His taste in anti-establishment music such as Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, and David Bowie, and his accompanying political views, set him apart as a dynamic, off-beat anti-hero.

Envision The Appearance Of Your Characters

If you yourself don’t have a clear sense of what your characters look like, then it’ll be near impossible for the reader to imagine them. You don’t have to list every specific detail. Allow the reader to use their own creativity.

However, it’s also vital to the overall impression of the character to know how they dress. Do they dress mostly according to their job? How do they display themselves in public, casual or fashionable. Is there something they wear that is of significant symbolic importance?

This will link into the character’s personality and provide the reader with greater insight into their mindset. The reader must be able to logically connect the various aspects of the character.

An example of clothing being a major signifier is the appearance of Jack Reacher in Lee Child’s novels. Reacher commonly wears very plain, practical clothes, often bought cheap so as to attract very little attention to himself. He uses clothes to downplay his size and strength. He wants to seem as ordinary as possible, so that when he gets into trouble he can completely surprise his opponents with his fighting ability.

Name Your Characters

Giving your character a unique or crazy name is a bit of a cheat to making them memorable. However, it’s still worth the thought. No one really gets excited by a character named John Smith. A name can also go some way towards shaping the general impression your character gives to the audience. For example, Inigo Montoya sounds flamboyant and heroic straight off the bat.

Consider this list of the fifty greatest literary character names as inspiration for your own characters. Furthermore, this in-depth character profile template will help you craft your characters more easily.

Write Your Character Into The Story

So now you know your characters, it’s time to integrate them into your story. As stated earlier, you can reveal your characters to the readers in three key ways:

Develop Interior Dialogue

Or more simply, thoughts. Literature has an advantage over film, in most cases, because it allows a writer to delve as deep as they like into the character’s head and directly relay their thoughts. Making use of internal dialogue is a quick way of giving the reader more information and understanding about a character.

Only the character and the audience knows what is going on in the character’s head. While you don’t want to over do it (show don’t tell!), it’s useful in circumstances where you want to show the opinions characters have of each other or the events that happen around them.

Inner dialogue is useful to contrast between what the character says out loud and what they are actually thinking.

Sherlock Holmes is famous for keeping a lot more within than he reveals to others. He holds his deductive reasoning in his head, leaving others puzzled as to how he’s joining the dots of the mystery at hand, until he is sure he has solved the problem. This is why he seems like such a genius when he reveals everything at the end of each story.

Create Authentic Dialogue

Dialogue is the most obvious way of displaying your character’s personality. Their delivery and vocabulary will reveal ample information to the reader, even through a simple conversation. How they converse with other characters is vital to their development and how the audience views them. Tone and inflection are everything.

In the dialogue of Arya Stark, it’s easy to identify her passion, petulance, and vulnerability, depending on where she is and who she is speaking to. In this excerpt she displays youthful innocence despite her otherwise feisty nature:

“I bet this is a brothel,” she whispered to Gendry.

“You don’t even know what a brothel is.”

“I do so,” she insisted. “It’s like an inn, with girls.”

– George R. R. Martin, A Storm of Swords

Talking to guards at a gate she displays her volatile temper:

“I’m not a boy,” she spat at them. “I’m Arya Stark of Winterfell, and if you lay a hand on me my lord father will have both your heads on spikes. If you don’t believe me, fetch Jory Cassel or Vayon Poole from the Tower of the Hand.” She put her hands on her hips. “Now are you going to open the gate, or do you need a clout on the ear to help your hearing?”

– George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

Dive Into The Action

Action is a simple and effective way of coercing your character to give away aspects of themselves. Someone slams a door, they’re angry. They runaway, they’re scared or embarrassed. They sigh, they’re disappointed or sad. All of these actions require no speech, yet they still demonstrate to the reader what the character is feeling and thinking.

Action is a great technique to use because it lets the reader play detective. Let them figure out why the character did what they did. This will give the reader satisfaction, when they find out they were right, or surprise, if they were wrong.

In Toni Morrison’s Beloved, we learn that Sethe tried to murder all her children in the past. At first we we struggle to think why she would do this when she seems to love Denver so much. The other events and circumstances allow us to guess at her motivations before they are fully revealed to us. The conclusion provokes the realisation that she was actually trying to spare them a life of misery as slaves.

Don’t Make Them Boring!

Just because your characters seem life-like, it doesn’t mean they’re interesting. Unfortunately, real people can be boring sometimes.

“I don’t know where people got the idea that characters in books are supposed to be likable. Books are not in the business of creating merely likeable characters with whom you can have some simple identification with. Books are in the business of creating great stories that make your brain go ahhbdgbdmerhbergurhbudgebaaarr.” – John Green

You need to give your character a compelling desire or need, a goal that will reel the reader into their story. It might be a story of revenge or mystery, personal redemption or emotional catharsis.

It’s also a good idea to shroud them in some mystery, such that the other characters and the reader can’t quite decipher them. This will keep readers intrigued. For instance, Captain Nemo in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea by Jules Verne is surrounded by question marks. We know very little of his past or where he got the money to build the Nautilus.

A good character also has to be surprising and unpredictable at times. An effective way to achieve this is to give them some contrasting personality traits. For example, they might be funny but cruel, kind but violent. This just keeps the reader guessing and elevates the tension in the novel.

Danny Kelly in Barracuda by Christos Tsiolkas patiently cares for the handicapped but possesses a violent streak that lands him in jail. Not an evil or dangerous character by any means, yet his violent trait develops from his personal demons regarding his sexuality, and the confusion and stigma that came with it.

Vulnerability is another perfect way to get the reader to interact with your characters and story. If a character is in pain or danger, it’s a human reflex to be drawn to them.

Morn Hyland in Stephen Donaldon’s The Gap Cycle is a character that suffers horribly at the start of the first novel. From that point on we are behind her all the way as she fights through the rest of the harrowing series, finding incredible strength to keep from breaking down completely while trying to care for a son that was born of rape.

It’s important to remember your character doesn’t necessarily have to be likeable, even if they are your main character, as long as the reader becomes attached to their narrative. Alex, the protagonist in A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess commits vile acts, including rape and manslaughter, but we still want to follow him to see if he can be redeemed.

Find Your Characters In The People Around You

When you think of all the different and interesting people in your life, it doesn’t seem so hard to dream up memorable characters. Family members, friends, acquaintances, enemies. All shapes, sizes, ages. You can take parts of all of them to help create authentic characters, while also drawing on your own thoughts and emotions.

In summary, the most important thing to consider can be summed up by Ernest Hemingway’s famous words:

“When writing a novel a writer should create living people; people not characters. A character is a caricature.”

The best way to do this is to make your character profile as detailed as possible, before you start your work. Happy writing!

***

Via : https://writersedit.com/fiction-writing/effective-ways-make-more-memorable-characters/