Writing a novel is hard, especially if you’ve never done it before. You’ve spent hours researching, building your world and becoming an expert on your characters. Now you’re ready for the next step: planning (also known as plotting).

While some people like to write organically (letting the story take you in whatever direction feels right), having a detailed outline can help make the novel-writing process a lot less daunting and overwhelming. But how exactly do you plan a novel?

Essentially, there is no right or wrong way to outline your novel. Each story is different and needs to be told in a different way.

However, if you need a bit more guidance on how to plot out the next bestseller you know you have inside you, the three-act structure might be for you.

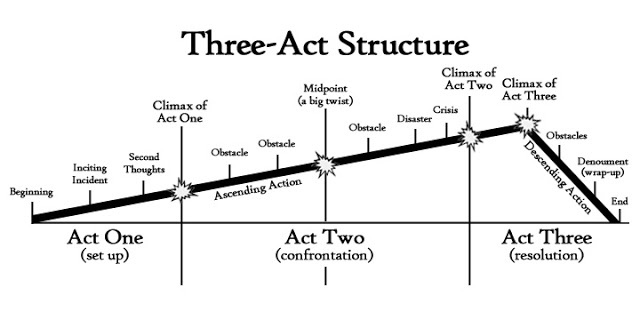

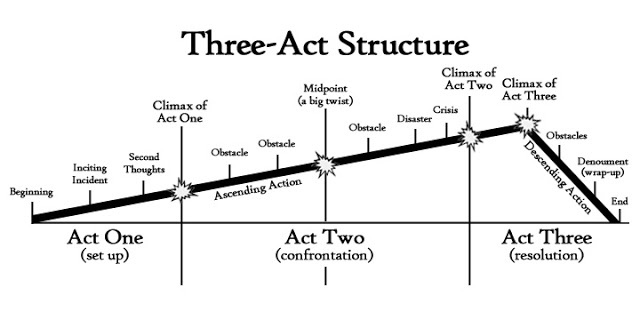

Defining The Three-Act Structure

The three-act structure is a popular screenwriting technique that revolves around constantly creating set-ups, conflicts and resolutions. With this structure, a novel is divided into three acts: a beginning, a middle and an end.

There are many versions of the three-act structure. In some, the middle is the same size as the beginning and end put together.

However, when you’re first starting out, it’s much easier to plan each act to be the same length. In this version of the three-act structure, each act is divided into nine chapters for 27 chapters in total. The nine chapters in each act are also split into three blocks of three chapters each.

This version creates a fast-paced novel that invites readers to keep turning your pages. If you’re still unconvinced, for an example Suzanne Collins’ bestselling young adult Hunger Games trilogy follows this structure almost perfectly.

Throughout this article, we’ll take a look at what each section of the three-act structure involves, using examples from The Hunger Games to demonstrate each element. (SPOILER ALERT: If you haven’t read or seen The Hunger Games and don’t want key plot points spoiled, read on at your own risk!)

Act One (set-up)

The first act is used to introduce the reader to the world your characters live in and to set up the coming conflict.

Block One – Introduce Hero in Ordinary World

- Chapter 1: Introduction (set up)

- Chapter 2: Inciting incident (conflict)

- Chapter 3: Immediate reaction (resolution)

In the first chapter, you need to set up your hero in their ordinary world. Introduce us to your characters and the relationships and conflicts between them. In The Hunger Games, the first chapter introduces the dystopian world and the Reaping.

The inciting incident in Chapter Two is the event or decision that sets your hero along the path of your narrative. The inciting incident is really important – without it, your story would not occur. The inciting incident in The Hunger Games is Katniss volunteering herself for the Hunger Games to save her sister; if Katniss didn’t volunteer, the rest of the novel would not have happened.

In the third chapter, the hero reacts to the inciting incident. The immediate reaction in The Hunger Games is when Katniss’ family and friends come to say goodbye to her before she leaves for the Games.

Block Two – Problem Disrupts Hero’s Life

- Chapter 4: Reaction (set-up)

- Chapter 5: Action (conflict)

- Chapter 6: Consequence (resolution)

Chapter Four is where the hero reacts to and reflects on the long-term impacts of the inciting incident. In Chapter Four, Katniss reflects on the impact her death would have on her community, especially her mother and sister. Katniss also starts to discuss strategy with Haymitch, her mentor.

As a result of their reflection, the hero decides to take action and do something to change their situation in Chapter Five. In The Hunger Games, Katniss takes her first step towards winning the Games in the parade of tributes. Her fiery dress and attitude win over the crowd.

Chapter Six details the immediate consequences of the action the hero took in Chapter Five. In The Hunger Games, Katniss discusses the success of the parade with Haymitch. She also reflects on her past and the difficulty of rebellion.

Block Three – Hero’s Life Changes Direction

- Chapter 7: Pressure (set-up)

- Chapter 8: Pinch (conflict)

- Chapter 9: Push (resolution)

The hero’s life has changed as a result of the action they took in Chapter Five, and this creates a lot of pressure and stress in Chapter Seven. The pressure is obvious in Chapter Seven of The Hunger Games. Here, Katniss has her demonstration where she shows the Gamemakers her archery skills by shooting an arrow towards them in frustration.

In Chapter Eight, the first pinch – or plot twist – occurs. A good plot twist is something completely unexpected for the reader. The first pinch in The Hunger Games is Katniss receiving a score of 11, something completely unexpected.

As a result of the pinch, the hero is pushed into a new world in Chapter Nine. The majority of this chapter in The Hunger Games centres around the television interviews with Caesar, the last formality before the tributes are sent into the Games. Here, Peeta declares his love for Katniss.

Act Two (conflict)

The second act is full of conflict. Character development is crucial in the second act; the hero at the end of Act One does not yet have the tools (whether those tools be emotional, physical or literal items the hero must retrieve) to succeed in the third act, so Act Two is all about the journey.

Block Four – Hero Explores New World

- Chapter 10: New world (set-up)

- Chapter 11: Fun and games (event/conflict)

- Chapter 12: Old world contrast (resolution)

Chapter 10 allows you to introduce the reader to the new world. What has changed, and how does the hero feel about it? In Chapter 10, Katniss finally enters the Hunger Games.

In Chapter 11, the hero can take a break and have a little fun. Maybe they have a date with their new lover, or maybe they do something they’ve never done before. Here, Katniss travels through the arena looking for water, and while she is still in an intense environment, she has a bit of a break.

Chapter 12 is time for the hero to compare their current world to how things were at the novel’s beginning. After realising Peeta has teamed up with her enemies, Katniss reflects on their relationship and compares this Peeta to the person she was friends with.

Block Five – Crisis of New World

- Chapter 13: Build-up (set-up)

- Chapter 14: Midpoint (conflict)

- Chapter 15: Reversal (resolution)

The fifth block is all about the midpoint, or the main crisis or conflict of your novel.

Chapter 13 is the build-up to the midpoint and Chapter 14 is the midpoint itself. A good midpoint will dramatically change the hero or impact their life in a negative way. In The Hunger Games, Katniss is pushed towards the Career tributes in Chapter 13, and escapes from them after Peeta saves her in Chapter 14.

Chapter 15 is the immediate reaction or consequence of the midpoint. Here, Katniss makes an alliance with Rue and they formulate a plan to take down the Career tributes.

Block Six – Finding a Solution

- Chapter 16: Reaction (set-up)

- Chapter 17: Action (conflict)

- Chapter 18: Dedication (resolution)

In Chapter 16, the hero reflects on the long-term impacts of the midpoint. In The Hunger Games, Katniss realises that to take down the Careers, they need to stop their food supply.

In Chapter 17, the hero decides to take action to resolve the problem created by the midpoint; however, they realise the enormity of their task when things don’t necessarily go to plan. In Chapter 17, Katniss blows up the Career’s food supply, but before she and Rue can celebrate, Rue is attacked by another tribute.

Despite the set-backs, in Chapter 18 the hero decides that they will succeed no matter what. Rue dies in Chapter 18, and Katniss promises to win for her.

Act Three (resolution)

The final act is all about resolutions. In the third act, the hero needs to find solutions to the conflict created by the midpoint, and you as the author need to make sure you tie up all the loose ends.

Block Seven – Victory Seems Impossible

- Chapter 19: Trials (set-up)

- Chapter 20: Pinch (event/conflict)

- Chapter 21: Darkest moment (resolution)

In Chapter 19, the hero faces significant trials. These trials are extremely difficult for the hero and is something the hero has never experienced before. Here, Katniss races to find Peeta and struggles to help save his injured leg.

Chapter 20 is the second pinch, where the hero experiences something completely unexpected that makes everything even worse. In Chapter 20, Peeta’s injury leads to blood poisoning.

This plot twist leads to the darkest moment in Chapter 21 where the thought of success is incomprehensible. Here, Katniss risks everything to get medicine for Peeta, and the chapter ends with her passing out from her own injuries.

Block Eight – Hero Finds Power

- Chapter 22: Power within (set-up)

- Chapter 23: Action (conflict)

- Chapter 24: Converge (resolution)

Having hit rock-bottom, the hero remembers their desire to succeed in Chapter 18 and finds the power within to continue on. In Chapter 22, Katniss and Peeta both start to recover from their injuries.

After deciding they can do it, the hero takes action in Chapter 23, and this action causes the plotlines to converge and come together in Chapter 24. In Chapter 23, Peeta and Katniss realise how close they are to winning, and in Chapter 24 all of the tributes are pushed towards the lake by the Gamemakers for the final battle.

Block Nine – Hero Fights and Wins

- Chapter 25: Battle (set-up)

- Chapter 26: Climax (conflict)

- Chapter 27: Resolution (resolution)

Block nine is the finale. In Chapter 25, the character has one last battle. This doesn’t have to be a physical battle – it could be a fight between friends or lovers, or a mental battle your hero has with themselves. Here, Peeta and Katniss try to survive the freezing night and kill Cato.

Chapter 26 is the final climax. The decisions the hero makes here will impact the rest of their life; it is the point of no return. In The Hunger Games, Katniss and Peeta pretend to eat the poisonous berries, which leads to President Snow stopping them by declaring them both winners. However, Katniss realises that despite winning the Games, she’s now in even more danger.

Chapter 27 is the resolution or the immediate reaction to the hero’s decision in the last chapter. Here, Katniss and Peeta finally get to go home.

The way you end your novel is up to you. You might choose to explain everything, or leave some things (or a lot of things) up to your reader’s imagination. It could be a happy heroic ending, or it could be a tragedy where everyone dies.

Either way, congratulations! You’ve planned a novel.

***

One last thing to note: When you start to plan your novel using this structure it’s important to remember it’s just a guideline. You don’t have to change your story to suit the structure; you can change the structure to suit your story. If your plot twist would make more sense earlier or later, move it. These aren’t hard rules. Do what is right for your story. So take a deep breath, set yourself up in your favourite place to write and start planning!

Via: https://writersedit.com/plan-novel-using-three-act-structure/